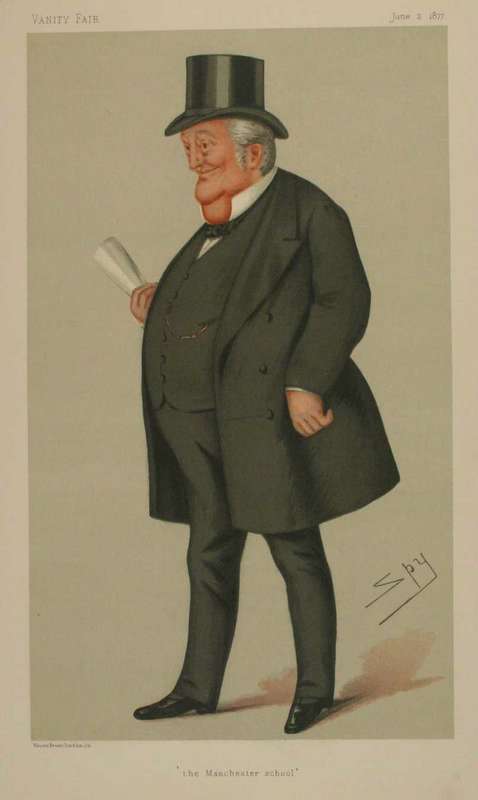

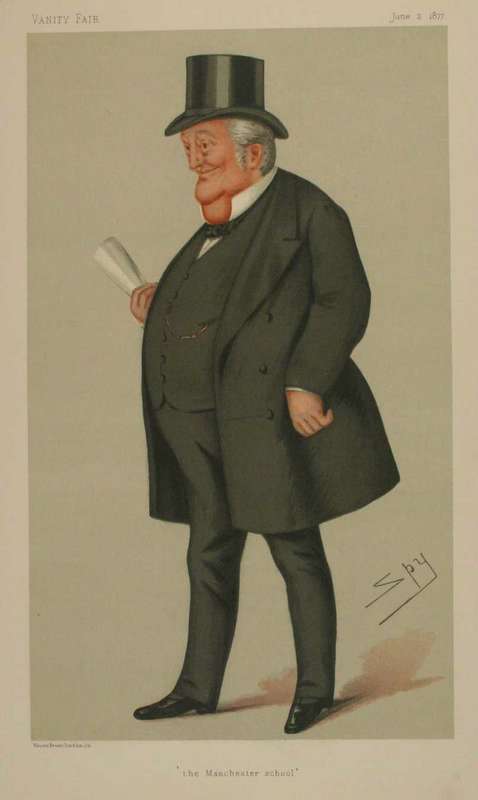

Thomas Bayley Potter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Bayley Potter DL, JP (29 November 1817 – 6 November 1898) was an English merchant in Manchester and

Thomas Bayley Potter DL, JP (29 November 1817 – 6 November 1898) was an English merchant in Manchester and

He was in

He was in

Thomas Bayley Potter DL, JP (29 November 1817 – 6 November 1898) was an English merchant in Manchester and

Thomas Bayley Potter DL, JP (29 November 1817 – 6 November 1898) was an English merchant in Manchester and Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

politician.

Early life

Born inPolefield

Prestwich ( ) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Bury, Greater Manchester, England, north of Manchester city centre, north of Salford and south of Bury.

Historically part of Lancashire, Prestwich was the seat of the ancient parish ...

, Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

, he was the second son of Sir Thomas Potter and his wife Esther Bayley, daughter of Thomas Bayley, and younger brother of Sir John Potter. Potter received his early education in George Street, Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

, then at Lant Carpenter

Lant Carpenter, Dr. (2 September 1780 – 5 or 6 April 1840) was an English educator and Christian Unitarianism, Unitarian Minister (Christianity), minister.

Early life

Lant Carpenter was born in Kidderminster, the third son of George Carpenter ...

's school in Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

. He subsequently attended Rugby School

Rugby School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) in Rugby, Warwickshire, England.

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school for local boys, it is one of the oldest independent schools in Britain. Up ...

under Thomas Arnold

Thomas Arnold (13 June 1795 – 12 June 1842) was an English educator and historian. He was an early supporter of the Broad Church Anglican movement. As headmaster of Rugby School from 1828 to 1841, he introduced several reforms that were wide ...

and then University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

.

In business

On graduating, Bayley went into the family business in Manchester. His father died in 1845, at Buile Hill, his home. His elder brother John, knighted in 1851, took over most of his father's role; the firm then traded as Potter & Norris. Thomas became the major partner in it when his brother Sir John died in 1858. He brought in as partner Francis Taylor (1818–1872), who had worked for Potter & Norris, around 1865, and the firm traded as Potter & Taylor. Not long after Taylor's death, Potter withdrew from business activity, to concentrate on politics.Liberal politics

Potter became Chairman of the Manchester branch of the Complete Suffrage Society in 1830. While he was generally aligned with the Radicals, there was a rift between their leadersJohn Bright

John Bright (16 November 1811 – 27 March 1889) was a British Radical and Liberal statesman, one of the greatest orators of his generation and a promoter of free trade policies.

A Quaker, Bright is most famous for battling the Corn Laws ...

and Richard Cobden

Richard Cobden (3 June 1804 – 2 April 1865) was an English Radical and Liberal politician, manufacturer, and a campaigner for free trade and peace. He was associated with the Anti-Corn Law League and the Cobden–Chevalier Treaty.

As a young ...

over the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

, which the Potter brothers supported; and Sir John Potter successfully stood against Bright in 1857. Potter, who was in many ways a follower of Cobden, tried to smooth matters over at the end of the 1850s.

In 1863 Potter was the founder and president of the Union and Emancipation Society. Initially simply the Emancipation Society, it was prompted by Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

that had freed enslaved people on 1 January 1863. Potter put his own money into the organisation, which adopted the pamphleteering publicity tactics of the Anti-Corn Law League

The Anti-Corn Law League was a successful political movement in Great Britain aimed at the abolition of the unpopular Corn Laws, which protected landowners’ interests by levying taxes on imported wheat, thus raising the price of bread at a time ...

, and ran frequent meetings. It was joined by prominent supporters of the Union in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, including Edward Dicey

Edward James Stephen Dicey, CB (15 May 18327 July 1911) was an English writer, journalist, and editor.

Life

He was born on 15 May 1832 at Claybrook, near Lutterworth, Leicestershire.

He was the second son of Thomas Edward Dicey, of an old Lei ...

, J. S. Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

and Goldwin Smith

Goldwin Smith (13 August 1823 – 7 June 1910) was a British historian and journalist, active in the United Kingdom and Canada. In the 1860s he also taught at Cornell University in the United States.

Life and career Early life and education

S ...

.

In 1865, Potter entered the British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 mem ...

and sat as Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MP) for Rochdale

Rochdale ( ) is a large town in Greater Manchester, England, at the foothills of the South Pennines in the dale on the River Roch, northwest of Oldham and northeast of Manchester. It is the administrative centre of the Metropolitan Borough ...

. This was the seat of Cobden, who had died that year. Potter kept it until 1895. In the House of Commons he was known as "Principles Potter".

Potter established the Cobden Club

The Cobden Club was a society and publishing imprint, based in London, run along the lines of a gentlemen's club of the Victorian era, but without permanent club premises of its own. Founded in 1866 by Thomas Bayley Potter for believers in Free ...

in 1866 and was honorary secretary until his death. He had proposed a "political science association" in a letter to J. S. Mill of 1864, taking as model the Social Science Association. It operated as a publisher, funded education in economics, and held an annual dinner, under a name suggested by Thorold Rogers

James Edwin Thorold Rogers (23 March 1823 – 14 October 1890), known as Thorold Rogers, was an English economist, historian and Liberal politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1880 to 1886. He deployed historical and statistical method ...

. It was fundamentalist about free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

.

A personal friend of Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patr ...

, Potter also supported Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

. The finance for Garibaldi's purchase of the island of Caprera

Caprera is an island in the Maddalena archipelago off the coast of Sardinia, Italy. In the area of La Maddalena island in the Strait of Bonifacio, it is a tourist destination and the place to which Giuseppe Garibaldi retired from 1854 until his ...

was arranged at a dinner given by him.

Last years

Potter was aJustice of the Peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

for Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

and Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

, and for the latter also Deputy Lieutenant. He sold the Buile Hill mansion to the Bennett family, and in 1902 it was purchased by Salford Council.

At the end of his life Potter spent his vacations in Cobden's old home, The Hurst, at Midhurst

Midhurst () is a market town, parish and civil parish in West Sussex, England. It lies on the River Rother inland from the English Channel, and north of the county town of Chichester.

The name Midhurst was first recorded in 1186 as ''Middeh ...

in Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

. He died there on 6 November 1898, aged 80, and was buried in Heyshott

Heyshott is a village and civil parish in the Chichester district of West Sussex, England. It is approximately three miles south of Midhurst. Like many villages it has lost its shop but still has one pubthe Unicorn Inn The hamlet of Hoyle is to t ...

four days later.

Family

Potter was twice married: *Firstly, on 5 February 1846, to Mary Ashton, daughter of Samuel Ashton, at the Unitarian Chapel ofGee Cross

Gee Cross is a village and suburb of Hyde within Tameside Metropolitan Borough, in Greater Manchester, England.

History

Gee Cross village centre dates back to the times of the Domesday Book. Originally, Gee Cross was the larger village in th ...

. She died in 1885, at Cannes

Cannes ( , , ; oc, Canas) is a city located on the French Riviera. It is a communes of France, commune located in the Alpes-Maritimes departments of France, department, and host city of the annual Cannes Film Festival, Midem, and Cannes Lions I ...

. Mary Potter was one of those petitioning in 1867 for a suffrage society in Manchester.

*Secondly, on 10 March 1887, to Helena Hicks, daughter of John Hicks Bodmin, at St Paul's Church, Lambeth, Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

.

Potter had four sons and a daughter by his first wife. The third and fourth sons, Arthur and Richard, and the daughter Edith, survived their father.

Thomas and Mary Potter were in the Unitarian congregation of Cross Street Chapel

Cross Street Chapel is a Unitarian church in central Manchester, England. It is a member of the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches, the umbrella organisation for British Unitarians. Its present minister is Cody Coyne.

His ...

. William Gaskell

William Gaskell (24 July 1805 – 12 June 1884) was an English Unitarian minister, charity worker and pioneer in the education of the working class. The husband of novelist and biographer Elizabeth Gaskell, he was himself a writer and poet, and ...

was an assistant minister there, to John Gooch Robberds, from 1828 to 1854 when Robberds died; his wife Elizabeth Gaskell

Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell (''née'' Stevenson; 29 September 1810 – 12 November 1865), often referred to as Mrs Gaskell, was an English novelist, biographer and short story writer. Her novels offer a detailed portrait of the lives of many st ...

published her first novel ''Mary Barton

''Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life'' is the first novel by English author Elizabeth Gaskell, published in 1848. The story is set in the English city of Manchester between 1839 and 1842, and deals with the difficulties faced by the Victori ...

'' in 1848. Mary Potter perceived a upsetting connection between the murder of her brother Thomas Ashton in 1831, a result of industrial tensions, and the novel's murder plot. The author denied any conscious use of Thomas Ashton's story, of which she knew, but the Potter family saw the plot device as referring deliberately to it.

Richard Ellis Potter

The fourth son, Richard Ellis Potter (1855–1947), was educated atEton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

, and at age 17 took part in the third of Benjamin Leigh Smith

Benjamin Leigh Smith (12 March 1828 – 4 January 1913) was an English Arctic explorer and yachtsman. He is the grandson of the Radical abolitionist William Smith.

Early life

He was born in Whatlington, Sussex, the extramarital child ...

's expeditions, in 1873 to Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), also known as Spitsbergen, or Spitzbergen, is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. North of mainland Europe, it is about midway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. The islands of the group range ...

. Letters that he wrote to his father remain.

He was in

He was in Dallas

Dallas () is the List of municipalities in Texas, third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of metropolitan statistical areas, fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 ...

in the 1880s, where he worked for Texas Land & Mortgage, a Scottish company managed by the Irish Courtenay Wellesley, as a valuer of land, and helped introduce the games of lawn tennis

Tennis is a racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent (singles) or between two teams of two players each ( doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket that is strung with cord to strike a hollow rubber ball cove ...

and golf

Golf is a club-and-ball sport in which players use various clubs to hit balls into a series of holes on a course in as few strokes as possible.

Golf, unlike most ball games, cannot and does not use a standardized playing area, and coping wi ...

to the city. He and his brother Arthur were both left money in 1887 under the will of George Scrivens, a family connection. He married Harriott Isabel Kingscote in 1899, and was father of Arthur Kingscote Potter.

In later life Potter resided at Ridgewood, Almondsbury

Almondsbury () is a large village near junction 16 of the M5 motorway, in South Gloucestershire, England, and a civil parish which also includes the villages of Hortham, Gaunt's Earthcott, Over, Easter Compton, Compton Greenfield, Hallen and ...

, in Gloucestershire. He became a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

in 1899.

References

;AttributionExternal links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Potter, Thomas Bayley 1817 births 1898 deaths Alumni of University College London Deputy Lieutenants of Lancashire Liberal Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies People educated at Rugby School UK MPs 1865–1868 UK MPs 1868–1874 UK MPs 1874–1880 UK MPs 1880–1885 UK MPs 1885–1886 UK MPs 1886–1892 UK MPs 1892–1895 Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for RochdaleThomas Bayley Thomas Bayley may refer to:

*Thomas Bayley (politician) (1846–1906), English politician

*Thomas Bayley (academic) (died 1706), English academic

*Thomas Butterworth Bayley (1744–1802), English magistrate, agriculturist and philanthropist

* Tom Ba ...